There Is No Art in Utopia. (2 of 2)

This blog post is the second of two about Utopia, Thomas More’s seminal book from 1516.

As discussed in my previous blog post, PART I, Thomas More’s book Utopia describes a distant island in which society is structured to promote equality and harmony. However, the title translates to 'not a place', in Greek, and More is ultimately launching an attack on the corruption of English society in the 16th Century. In this two-part blog post, I am interested in More’s views on housing, art and architecture.

Headpiece from Sir Thomas More’s Utopia (1518).

Architecture

Utopia is prolific for its reimagining of the built environment and how this can restructure society. One of the most controversial offerings from Utopia is the analysis of land ownership and architecture. More describes a situation in which there is no private property and all space is designed in a state-sanctioned modular fashion:

“In Utopia, where there's no private property, people take their duty to the public seriously.”

As we will see with all Utopian design, the architecture is described as simple, utilitarian, and without ornamentation. All houses, towns and cities are modular in form and there is no distinction between the houses of the rich and poor, reflecting an emphasis on equality. Residential areas are clustered around central squares, with the design encouraging interaction among neighbours, similar to Grecian agoras. There is an emphasis on quality of life, with wide streets, well-ventilated houses, and sanitary conditions. Materials are locally sourced and sustainable. So far this all sounds wonderful. However, red flags begin to emerge when More describes how households, towns, cities and colonies are organised. We begin to get a sense that freedoms might be compromised with limits on population in households and regions:

“Each town consists of six thousand households, not counting the country ones, and to keep the population fairly steady there's a law that no household shall contain less than ten or more than sixteen adults - as they can't very well fix a figure for children. This law is observed by simply moving supernumerary adults to smaller households. If the town as a whole gets too full, the surplus population is transferred to a town that's comparatively empty. If the whole island becomes over-populated, they tell off a certain number of people from each town to go and start a colony at the nearest point on the mainland.”

Civitas Veri, or City of Truth, by Bartolomeo Del Bene (1609).

The Utopians seem to be treated rather like cattle here, being divided up into pens and moved around based on numbers rather than relationships or preferences. Furthermore, they are not allowed to stay housed in one place for more than a decade, at which point they are shipped off to a different house in order to quash attachments to specific properties. In a similar vein, specific trades are practised by certain households, and if a child wants to learn a trade practised by another family, they are sent away from their biological family, and to a new one, which adopts them. This device can be seen emulated in The Divergent, the dystopian teen books and films.

You are not even allowed to visit another town without permission from the state, and if permission is granted, you are sent out with a group of others on a collective passport. In this way, everyone keeps a watchful eye on each other, and anyone who fails to return in the allotted time will be located, brought home in disgrace, and possibly put into slavery. Yes - Utopia has slavery. It is a construct more like community service, and the slaves can work their way out of slavery, but is an ever-present threat for anyone diverging from the utopian way. Hythloday, More’s imaginary guide to Utopia, labours this point, explaining:

“You see how it is - wherever you are, you always have to work. There's never any excuse for idleness. There are also no wine-taverns, no ale-houses, no brothels, no opportunities for seduction, no secret meeting-places. Everyone has his eye on you, so you're practically forced to get on with your job, and make some proper use of your spare time.”

This social commentary appears to be targeted at “members of so-called religious orders [and] the rich, especially the landowners, popularly known as nobles and gentlemen”, who More essentially describes as “insatiable gluttons”, and likely to avoid work at all costs. More does emphasise that labour should be reduced to a minimum and suggests that workers use their optimised leisure time to watch public lectures and educate themselves. From this perspective, the protocols are framed in a fairly attractive way to the working person.

Cover of George Orwell’s 1984 (1949).

However, in light of Republics with similar structures, such as North Korea, these restrictions become quite sinister. Sometimes my best ideas come to me when I’m sneaking around doing things I really shouldn’t be doing - or doing nothing at all, in fact - just exploring aimlessly. I was struck by how slippery the slope is between utopia and dystopia - and this is especially true in the discussion of art, entertainment fashion, and the organic production of culture. In recent decades, Authors such as George Orwell and Margaret Atwood have created fictional dystopias inspired by this type of state control. In my view, on the left, we often know what we find unacceptable, but are unable to create a viable alternative. We are seeing this now with Critical Theory and the removal of public monuments. I became interested in what More has to say on this topic, as I will now discuss.

Public monuments in Utopia.

Public art in Utopia is an especially interesting topic for me since this is the domain in which I have built my career, and have been conducting my research with the University of Cambridge. In the world today a kind of proxy war is being fought with public monuments due to recent protests over racial equality and social justice. Specifically, statues relating to the US confederacy, British Colonial rule and slavery have prompted a renewed sense of urgency in the UK and the US to reevaluate the messaging in our public spaces. In Utopia, the entire urban infrastructure has been imagined to facilitate a democratisation of space and lifestyle, however, I could only find one paragraph about public monuments, which are often seen as urban pillars of shared memory and values:

“[...]they put up statues in the market-place of people who've distinguished themselves by outstanding services to the community, partly to commemorate their achievements, and partly to spur on future generations to greater efforts, by reminding them of the glory of their ancestors. But anyone who deliberately tries to get himself elected to a public office is permanently disqualified from holding one.”

This is an interesting offering from More as it emphasises a need for humility in the population. Individuals who are seen to self-promote or campaign to be mythologised will never see themselves in stone.

Statue of Confederate General Robert E Lee being removed in 2021.

There is no mention of hereditary rights, such as monarchy, and I am curious to know what Thomas More’s contemporary, King Henry VIII, must have thought about this passage - bejewelled and standing proud in monuments across the land. So what do Utopian monuments look like? Well in the Utopian artwork itself, we do not see democratisation in the same way as in the architecture - it is still espousing the same kind of figurative, state-sanctioned, hero-worship that would have been common in 1516, and that we still see today. Virtually all civic monuments seem to fall into the same formula, whether they be Communist, Capitalist, or some other -ist. When I lived in Berlin I used to see the colossal head of former Communist party leader, Ernst-Thälmann, outside my kitchen window.

Also, notice how the pronouns describing the statue are male. Monument Lab, a US-based studio, logged and examined 50,000 U.S. monuments in the US in 2021 and found that of the 50 individuals represented most frequently, 88% were white men, 50% were slave owners, 6% were female, and 10% honoured Black or Indigenous figures. My current research is concerned with practical solutions for reimagining public monuments to represent masses of people, rather than individual hero worship. My artwork A Dangerous Figure, and the representation of the mass young unemployed, led me down this road of inquiry.

Back to Utopia. Next, I was interested to know about how Utopians were able to express themselves with fashion.

Henry VIII statue, University of Cambridge, Kings College.

No fancy pants in Utopia!

On the subject of fashion, Hythloday is fairly vague, stating that summer clothes are made of “thin stuff” and winter clothes are made of “thick” stuff. Enlightening. Utopians are apparently “content with a single piece of clothing every two years”, which would be “neither sumptuous nor sordid”.

The fashion cannot change, because it is regulated, and is "neither disagreeable nor uneasy". The only piece of flair the Utopians are allowed is a badge showing what job they shoud be doing and what level they are. This is all in the name of equality. Furthermore, all clothes are unisex so that “no sex may be distinguished by their habits”. In terms of gender politics, is it also interesting to note that Utopian women were said to work and share the same jobs as men, such as sewing, craftsmanship and farming, which was extremely progressive in 1516. Women are even allowed to be priests in Utopia, “although”, Hythloday explains, they “aren't often chosen for the job, and only elderly widows are eligible.” He does, however, still describe women as the “weaker sex” and proclaims the eldest man to be the head of each household. Although I understand the egalitarian rationale for this uniformity in fashion, it reads like a prison scene in which everyone is wearing working overalls. It is not difficult to draw links between Utopia and various totalitarian states to follow in the next 500 years. There are, however, some in Utopia who are allowed to be more expressive with their clothing. These are slaves, babies, and the clergy, as I will discuss.

Plate from Utopia (1516).

In Utopia, expensive materials and fancy clothing were often presented as the objects of ridicule. In order to deter Utopians from opulence, slaves were accessorised luxuriously:

“They also use chains and fetters of solid gold to immobilize slaves, and anyone who commits a really shameful crime is forced to go about with gold rings on his ears and fingers, a gold necklace round his neck, and a crown of gold on his head.”

The idea is that precious metals should not be used to glorify individuals, but should be used for the betterment of society as a whole. Therefore, expressions of wealth and pride are transformed into a kind of circus, meant to provoke distain.

Plate from Utopia (1516).

Children are also given extravagant jewels and gold chains to play with, so that these things would be associated with childishness and something that every adult should grow out of. When you look at the intentions behind these restrictions in fashion, they are clearly noble, and More discribes a land where the locals are disgusted by inequality and sycophantry:

“But what puzzles and disgusts the Utopians even more is the idiotic way some people have of practically worshipping a rich man, not because they owe him money or are otherwise in his power, but simply because he's rich - although they know perfectly well that he's far too mean to let a single penny come their way, so long as he's alive to stop it.”

This must have really annoyed the King, which I am totally on board with. However, I could never live like this. I do not believe it is in our nature to homogenise every aspect of our lives. Perhaps, I would mind less if the claims were at least consistent across all Utopians, but the clergy appear to have clothing which is quite a lot more elaborate than everyone else! Hythloday explains that:

“The congregation is dressed in white, and the priest wears multi-coloured vestments, magnificent in workmanship and design, but made of quite cheap materials - for instead of being woven with gold thread, or encrusted with rare jewels, they're merely decorated with the feathers of various birds. On the other hand, their value as works of art is far greater than that of the richest material in the world. Besides, the feathers are arranged in special patterns which are said to symbolise certain divine truths…”

The materials may be cheap, but skilled craftsmanship is not. I find a great contradiction here. In this respect, you get a sense that More doesn’t really hold a lot of value in skilled craftsmanship, and with this disparity in clothing, a subtle hierarchy appears to be seeping through the cracks of Utopia. So I find myself asking, does human nature ensure that true equality is an impossibility?

Utopia or Dystopia?

More’s Utopia has beautiful intentions. There is an awful lot with which I agree, however, I believe the implementation of his system would mean the destruction of freedom and resemble something far closer to a dystopia. There has been rich discussion over Utopian ideals in the following centuries, from the Communist ideologies of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and the realisation of utilitarian brutalist architecture, to the dystopian fiction of George Orwells’ 1984, and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

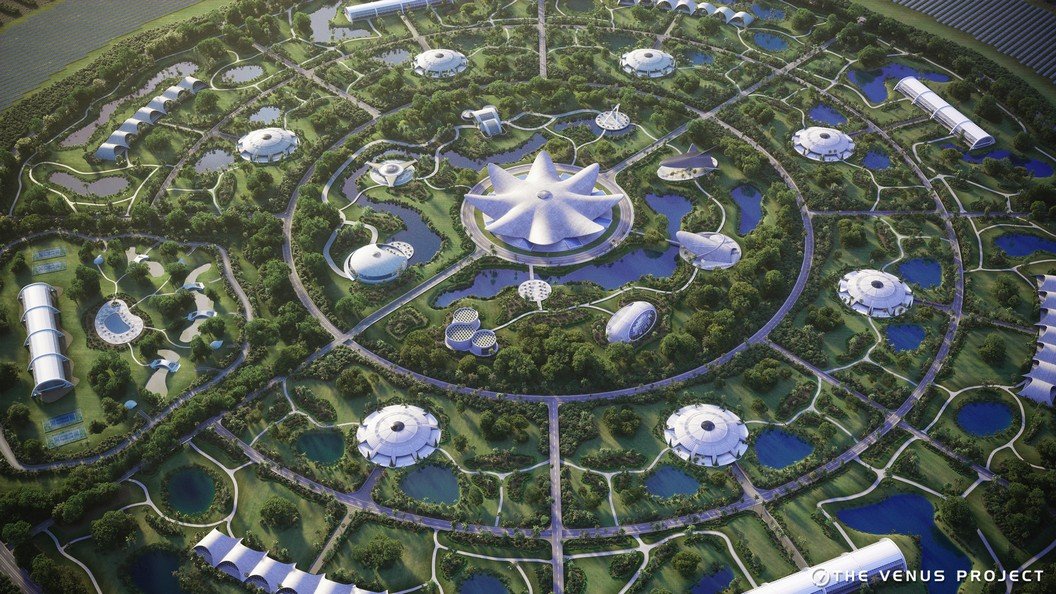

A direct link to More’s Utopia is the aspirational architecture of Jacque Fresco’s The Venus Project. Films such as Equilibrium and Fahrenheit 451 focus specifically on the destruction of art and the individualistic imagination, which, as an artist, I find particularly sinister. With every form of work, entertainment and expression so tightly controlled in Utopia, all under the watchful eye of neighbours, there would be no space for genuine culture to sprout.

Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate, London (1968).

Utopia allows for only one model for fashion, one model for architecture, and virtually no mention of any sculpture, painting or illustration. This leaves More’s Utopia feeling incredibly austere in my eyes, and because of this, I have concluded that in More’s Utopia, there is no art.

My Utopia!

Two years ago I envisaged my own Utopia, creating an audiovisual artwork called Power from the Blazing Stone. This was a commission from a Lithium Mine in Cornwall and was set against a backdrop of complexities to do with ethics in the mining industry, the history of oppression faced by the Cornish people, and the mythical folklore of the region. Similar to More, I described a world in which private ownership of land was no longer a reality, but every child had a powerful piece of technology tethered to them in order to fulfil their every need. The adults, however, had mysteriously disappeared… Following the launch of my artwork, I began to receive comments suggesting that I was helping to enslave humanity for a new world order:

Genuinely interesting. YouTube automatically hides comments like this, but in many ways, I am just grateful for the interesting interactions. Please go and have a listen with this link, play the game with this link, leave me a comment, and let me know how I did. The entire series is free.