Ornamental Hermits and Alchemist Hens. Why I reversed the narrative of Jack and the Beanstalk to write Alexander in Mimesis.

This blog post contains spoilers for Alexander in Mimesis. If you haven’t already listened then hop over to Apollo Podcasts, Apple Podcasts, Audible, Amazon Music or stay right here on my site, and give it a listen! If spoilers don’t bother you, then read on…

I extracted Alexander in Mimesis from encounters with graveyards, bars, museums and research labs. As I explored Manchester, NH, the story revealed itself in pieces and I tried to let the space guide me. What I didn’t expect, however, was to end up writing my own anti-Jack-and-the-beanstalk in order to grapple with the darker aspects of capitalism. As an artist, I’ve always been conscious that I occupy an unusual place in the world of work, and after the covid apocalypse, the idea of value and payment really came to the fore. I sought to discuss this somehow and was searching for a vehicle. Eventually, I decided to reverse the analogy of capitalism embedded within "Jack and the Beanstalk" to shed light on the challenges creatives face in a commercial world.

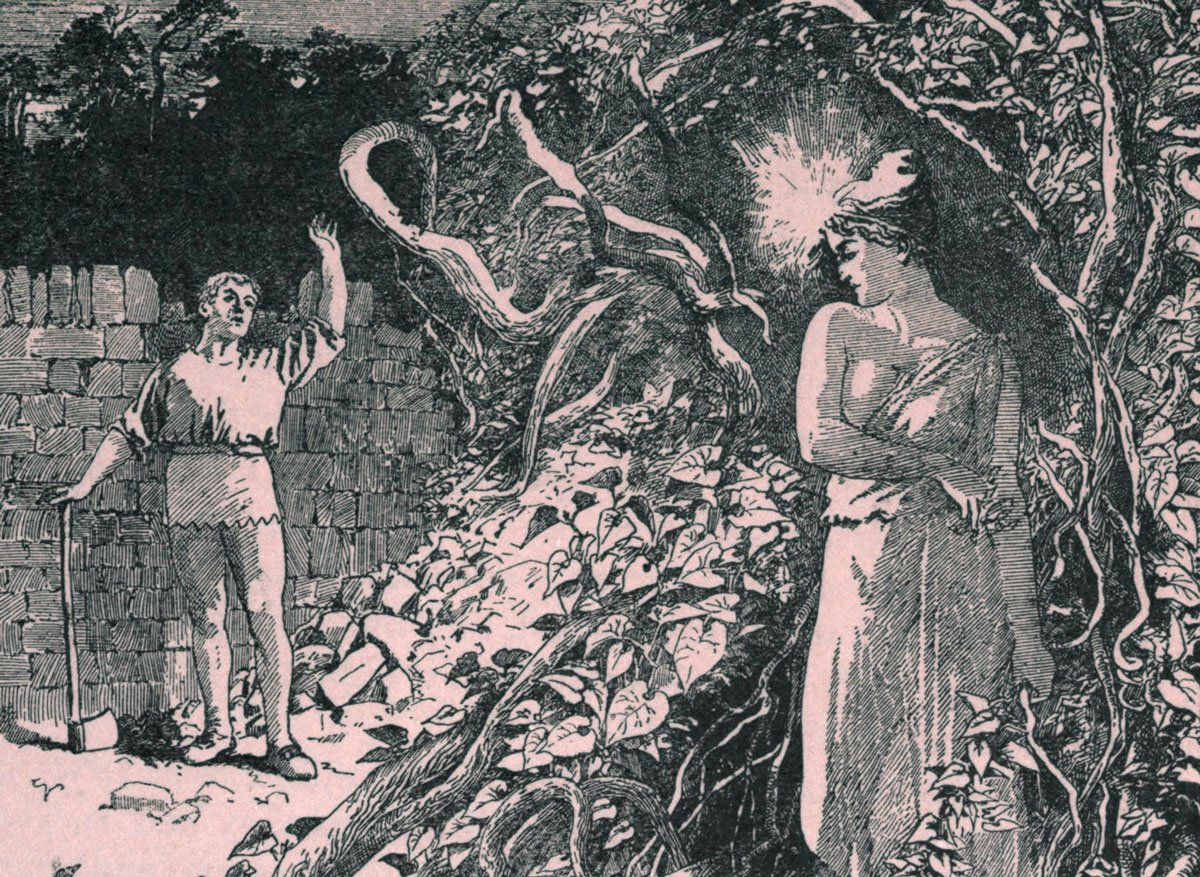

Jack the Giant Killer. Illustration by Hugh Thompson (1898).

I turned the golden egg-laying hen into the main character and presented Jack and the giant as opposing parts of the same unstoppable force. So let me tell you my thoughts on the story and how I adapted it…

Illustration by Walter Crane (1865-1915).

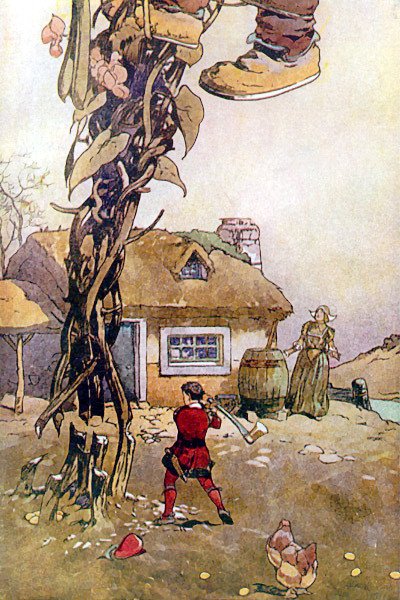

Jack and the Beanstalk presents the misery of working-class poverty whilst promoting risky investment as a viable road to a happy ending. Jack and his mother are impoverished farmers. Jack’s mother asks him to sell their only asset for money, but he trades it for beans instead. Angered, Jack’s mother recognises these beans as worthless, but little does she know that they represent the optimistic, gambling spirit of entrepreneurship (lucky!). The beans sprout into a towering stalk of capitalist enterprise, providing our hero with the opportunity to climb above the clouds, traversing the class boundary, and up to a giant’s castle, representing the wealthy elite. Jack steals the golden egg-laying hen from the giant, i.e. the means of production, and chops the beanstalk down so the giant topples to his death.

The positioning of the giant parallels the annexing of wealth and power in capitalist societies, with a few individuals or corporations exerting significant influence over the economy. Jack becomes a kind of Promethean saviour, releasing some of that godly wealth to himself and his mother. A working-class hero. The beans were never beans, they were risky investments which leveraged Jack into wealth, and in the end, the golden egg-laying-hen becomes a kind of passive income from which Jack and his mother can live charmed lives till they pop their clogs. Jack had to lie, gamble with assets which did not belong to him, break and enter, steal, and commit murder to achieve this - and thus, completes his character arc from proletarian into the new bourgeoisie.

Illustration of Jack And The Beanstalk in The Red Fairy Book (1890), Henry J. Ford.

Jack And The Beanstalk. Illustration for The Book of Nursery Tales with introduction by Compton Mackenzie pictured by HM Brock (Frederick Warne, c 1910).

Jack and the Beanstalk extolls the virtues of becoming a risk-taking, amoral adventurer - a yuppy, basically. If you need an example in the modern age, look at stock market investors, or 90% of tech startup CEOs. Heralding such a protagonist always felt strange to me, and as I grew older I realised that Jack and the Beanstalk served as an analogy for capitalism, with the values of a pyramid-shaped social structure at its heart. It offers an unattainable path to success on the one hand and staggering wealth disparity on the other. I think of the lottery system in Orwell’s 1984 - and although I recognise that’s a critique of communism, I think the analogy works better with capitalism - ironically.

Jack’s usurping of the giant is a symbolic changing of the guard and an indication of healthy competition within the thriving marketplace. Jack is not fighting the market system, he simply wants to be the one at the top of it. There is no agent in this story fighting against the unequal distribution of wealth - the system itself. Our job as spectators is to cheer Jack on as he becomes an elite manager of capital, as opposed to a value creator, inventor, worker, artist, or labourer.

Interestingly, the closest representation we get of the creative spirit is the hen that lays golden eggs. It is tempting to think of the hen as an alchemist, but symbolically I see it as the worker. The hen represents us, the normal people, the factory line workers, the builders, the teachers and nurses, the shop workers and bank tellers, the product designers and artists, scientists and engineers; those with expertise who sell their knowledge and time. The animal represents us - without a voice - we are the property that Jack wants control of.

Warne's National Nursery Library (1870).

Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1918 edition of English Fairy Tales.

This realisation became the foundation for my work, Alexander in Mimesis. In my reversed narrative, the hen takes centre stage, emphasising the careful craftsmanship of the golden eggs. Alexander in Mimesis follows me creating the story of Alexander in Mimesis. In this sense, the resulting artwork is the golden egg, so the concept is cyclical, hence “Mimesis”. Jack and the giant merge into the outer world of the giants-in-the-sky, the Mimesis factory, triggering a larger discussion about the art world's place within the capitalist market - fish in a barrel who dream of other worlds. Do artists truly experience freedom of thought and expression? I would say that every artwork is a compromise between the brief, funding, available resources, the skills you’ve got, and the market. In many ways, Artists are actually more bound by capitalism than anyone - with successful artists selling directly to the very richest giants! These artworks are status symbols and hold cultural collateral - or mana. In this sense, I think the idea of artists as free is a fallacy. The golden-egg-laying-hen seems a good analogy.

I think subliminally I was also questioning the nature of artist residencies, in which artists are housed in foreign lands to generate a kind of cultural capital by simply being and doing - a kind of magic mana. At their best they can be temporary safe harbours for artists; facilitating inspirational adventures with new experiences, resources and networking opportunities - and most are highly competitive. In this sense, the artist becomes almost like one of those “Garden / ornamental hermits” from the 18th century who lived inside the rockeries of wealthy landowners and were viewed for entertainment, or occasionally asked for their wise advice. There is a peacefulness to it, but very it’s passive in nature - just like the giant’s hen. It is a position of prestige, but usually not one of power. Sometimes I think of it as being like a firefly in a jam jar, with which someone might light the darkness a little.

I am planning to explore the idea of the artist as a producer of mana in my next project - so this is very much on my mind these days.

John Bigg, the Dinton Hermit.

18th Century depiction of a Garden Hermit.

So the key drama in Alexander in Mimesis becomes the mystery surrounding mana - what is Alexander generating? How could this currency be profitable to the giants and not to Alexander himself? If Alexander is the hen, then who is he laying for? And so we embark on a much larger discussion - how is value measured and sold in the art world as a subsidiary of the capitalist market, and how do artists fare considering their presentation as more spiritual / ornamental than commercial? Alexander is, himself, one of these giants, and has ultimately placed himself into a box - a position in which he is able to create, and outside of which he could not survive. So this begs the question: will Alexander escape the fate of the hen? Can he break the cycle and become an agent of his own fate? Or will he bounce from owner to owner, laying eggs for the consumption of others for the rest of his life? This is the key question repeated continuously by the turkeys. Can we find a better system than capitalism? I have no idea, and Alexander in Mimesis is an invitation to hear my utter confoundedness at the whole machine.

Finally, it is no coincidence that I had wild turkeys raising these questions over freedom and capitalism since I had only ever encountered farmed and slaughtered turkeys until I arrived in New Hampshire in 2021. Seeing fowl like this, roaming boldly, was a revelation for me - it seemed like a win for freedom. They were precisely not like the hen in Jack and the Beanstalk, but quite brazen, and I became obsessed with visiting them for as long as I could brave the cold. I do believe humans could set themselves free - if we only reorganised our resources to benefit the many rather than the few, and allowed machines to take the bulk of our manual labour, and AI to tackle the bulk of our managerial work, without casting the unemployed into poverty…

Anyway, “Live Free or Die, New Hampshire!”, whatever freedom means.

If you have not already listened to Alexander in Mimesis yet, be sure to give it a listen now!